I have been on Twitter since 2006. I originally joined because I had a crush on Neil Gaiman. And then he married Amanda Palmer. Then I had a crush on Amanda Palmer. Since then I've organically grown my following to about 850 real people, mostly writers and readers and lovers of Folklore. It's been a space where, unlike Facebook or Instagram, I have been comparatively encouraged to be myself. I have heard it said that Twitter is where people go to become brands, and brands go to become people, but there is a side of Twitter that encourages authenticity and values the personal journey. I have always found Instagram to be a place of inspiration and creativity, much like TikTok, but also like TikTok, Instagram is a place where complexity and reality is hidden cleverly beneath very shiny and polished exterior, like a beautiful car with a crap engine.

Facebook is just where I go to see my friends, real people that I've met and developed relationship with, though even a relatively intimate relationship online is always going to be clouded by the persona people wish others to see.

Twitter has become a place of support and community, especially for the #WritingCommunity, where we lift each other up for exposure and often become consumers of the hobby we ourselves practice. I've been happy to meet and promote the works of many Indie authors in that space.

Twitter On The Edge

|

| Twitter on the Edge |

https://www.fastcompany.com/90813862/twitter-closing-update-musk-news-whats-happening

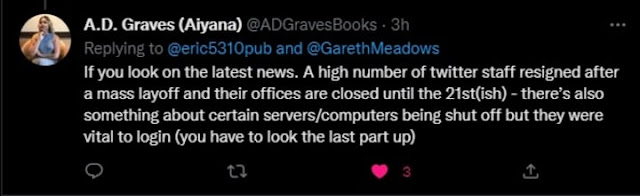

The above gives a decent-ish run down of the concerns users are having about how well the software can run on so few people with offices closed.

It is true that large teams of people are needed to keep big platform apps like Twitter running, but there's a lot that people don't seem to understand about how large distributed systems work that makes me think the idea of Twitter slowing down, or shutting off as a result of no one being in the office, is a load of bupkiss.

Twitter Is Software

Like most apps, and anything we use that is a human-interactive interface--called a user interface--there is a complex software underneath the smooth and hopefully enjoyable set of images, text, links, buttons, and however many dozens of interactions that make up the exterior of an application. This complex system requires dozens of people working either together or independently to function under normal circumstances: the addition of new features, the maintenance of old code, the upkeep of hardware, the scalability of architecture, proactive--and sometimes reactive--defenses against external attack. Taking this logic into account, with so many layoffs, strikes, and lockouts, it stands to reason that without everyone having their eyes on the software all the time that it's only a matter of hours before the entire thing falls to pieces.

Yeah...... no.

You see, in the wide world of scalable distributed systems, much of these processes needed to ensure there is enough bandwidth to handle intense load, space to handle increases of data, and protections against cyber attack are largely automated. Case in point, an organization might employ a series of load balancers hosted in the cloud (should they choose to do so) that can be templated to spin up and spin down "instances" needed to distribute intense load. Once load drops off, the "instances" shut themselves down. That is all wiiiiiiildly over simplified. And dubiously accurate (I'm an SRE, not an architect--and not even a really good SRE, just one with some visibility and experience with cloud hosted apps). Databases and hard drives can be backed up on snapshots or redundantly backed up physically (if you insist on doing it the hard way). Software patches for most operating systems are monthly updates if we're not talking bug hotfixes, and monitoring, either third-party or built internally--or a combination of the two--helps folks like DevOps/SRE to see where something is going wrong: "some process is eating up a lot of memory, better reboot that server," or "that machine doesn't usually run that hot. Looks like something is eating up a lot of CPU. Better start checking the logs."

The Difference Between Development and Maintenance

There are a lot of people, some people in the tech industry even, throwing around the word "dev". The devs have been locked out of Twitter offices. The devs are being worked to death or potentially could be if they stay on at Twitter. The devs this. The devs that.

Do you have any idea how little work devs do when they are not developing? Development is involved in maintenance, but really developers work on producing a stable and reliable piece of software with a reasonable number of new features and is often involved in speeding things up on the back end to make the use of the app overall more enjoyable. No one wants an app that's got 100% uptime but takes forever to load anything. No one wants an app that's got 100% uptime but the front-end design hasn't changed in 20 years. Something is always shifting and changing, and that requires developers.

But when things are stable, i.e. there is a 99.99% uptime (Google suggested service level objective), and no new features or improvements are being made, devs do relatively little work on a software. When no new development is taking place within a software's infrastructure, responsiveness, user interface, data engineering, or communication methods (i.e. how it speaks to exterior and interior systems), devs are largely not needed.

Conclusions

So when I hear stories of devs and teammates at Twitter being locked out, layed off, severed, or any other of the human horrors He Who Shall Not Be Named seems capable of doing, I hear human voices. I hear human anger. Who do I not hear screaming? Software. Because it's not a person. It's a complex system with probably hundreds of fail-safes built into it (unless they're reeeeeeeally dumb) to keep it going in the events humans stop touching it. Humans stop touching Twitter every night, over holidays, and during code freezes (like we might be experiencing now). It doesn't wind itself down, run out of steam, require someone to go down into the server banks and wind them back up, or slowly grind to a halt in a matter of hours. Something has to happen, and if that something does happen, automation can handle it, or if it can't, very few people are needed to respond.

So no, I don't think Twitter will be dead by Monday. I think a lot of people are coming to grips with how megalomaniacal Elon Musk is, and how disconnected he is from his peers. I think the real tragedy is not that Twitter could be severely impacted by his decisions, but that we have become so ingrained and dependent on our social media that this might actually be a problem for us. The problems facing the world today requiring true intervention would require us all to put down our phones and pick up a weapon to defend freedom as we know it.

Twitter dying isn't one of those.

Comments